By Nick Hainsworth

Language is another way we can trace the origin of our species. Think about the word “dog” for a minute. Why is it that when English speakers say the sounds in the word “dog,” a picture of a dog comes into our mind? There isn’t anything about the sounds themselves that has anything to do with the creature. Indeed, other languages will have a different word for dog. Why then, do when I say or you read the word “dog,” all English speakers know what I’m talking about? This is what we mean when we say that language is symbolic. The sounds in “dog” symbolize a kind of thing, and we all understand that thing to be a dog. Taking a step away from the dog example, who decided what words mean what?

This question is driving at a greater debate, which is, how did language originate? What was the organic process that led to a community of people collectively understanding what sounds symbolized? In some ways, the debate is more theoretical than scholarly. While we can study archeological records of the first written languages, there is no evidence we can find for the first spoken languages. However, there are linguistic patterns that can give us clues.

To understand our linguistic clues, we need to understand a linguistic term called phonemes. A phoneme is the smallest unit of speech that can distinguish one sound from another. For example, the words “tap,” “tab”, and “tag” are all separated by just one phoneme.[1] Some languages have an incredibly high number of separate phonemes, while others have comparatively less.

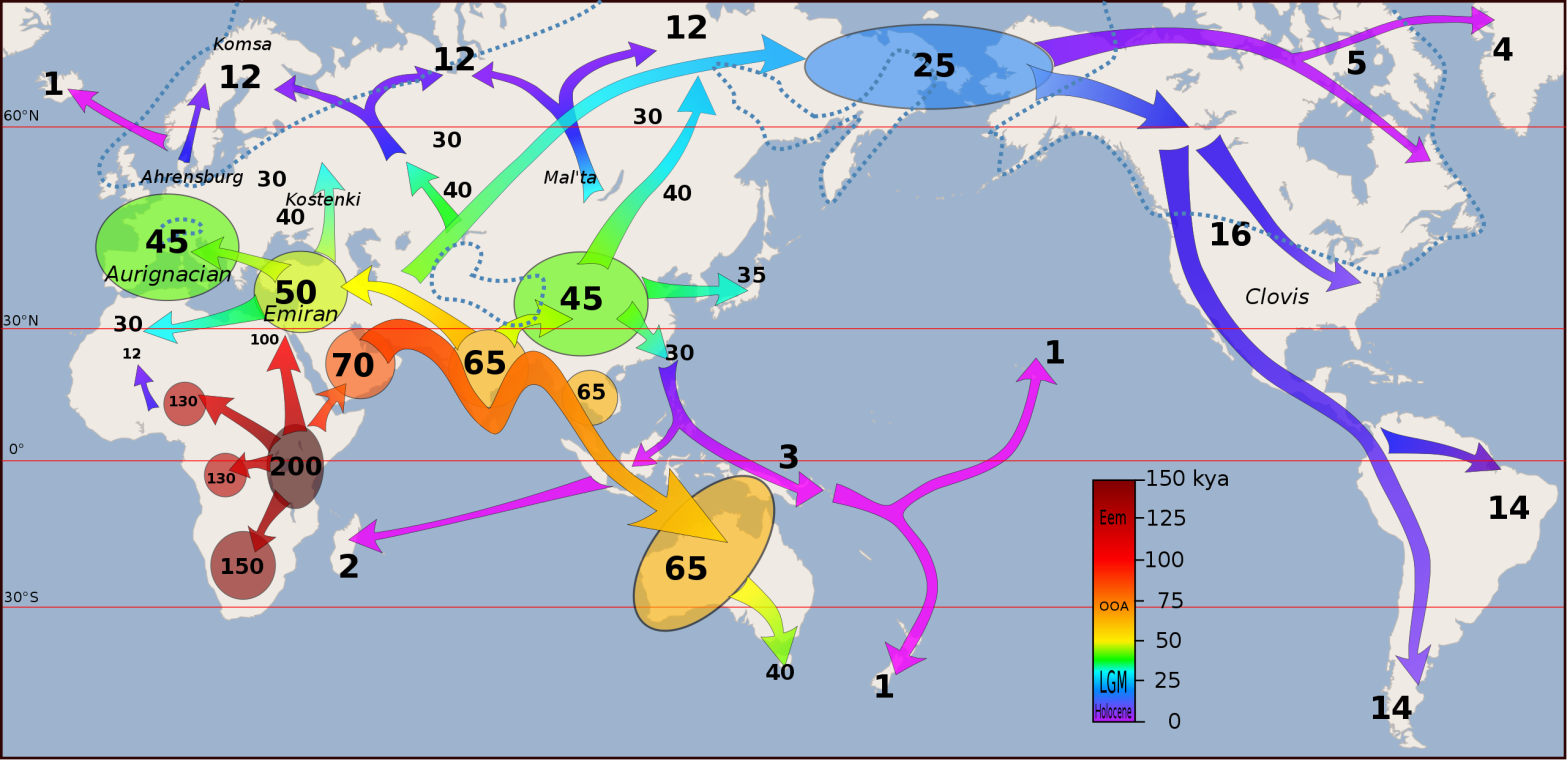

Turns out, there is a pattern to how many phonemes a language has. African languages have an incredibly high number of phenomes, and the further you get from Africa, the less phonemes a language has. For example, Indigenous languages in Oceania have very few phonemes compared to African languages. This is very similar to the pattern we find in genetic diversity. Not only did humans become less genetically diverse as they traveled away from Africa, but their language did as well.[2] Similar studies have traced how long it takes phonemes to naturally develop, and they can use this period as a clock to determine how long-ago language first began appearing. Using Africa’s oldest languages, these studies have postulated that the phonemes in these languages first began appearing around 50,000-150,000 years ago, around the time Homo sapiens became a species.[3]

In this three-part blog series, we’ve learned a lot about the origin of the human species. But how does the origin of our species relate to geography? The first obvious answer is that physical geography affected how our species evolved, where we migrated to, and the survival of people and the languages and culture they carried. It also reminds us that humans are just like any other animal on the planet. As much as we might want to or try to, we can’t totally control nature or our physical environment. We still need to live next to water to drink and find food to eat. But secondly, and perhaps most importantly, it’s important to remember that all humans share a similar story. We learned to survive in a place and speak in a language. We all have the same ancestors. Even though you might think your neighbor looks a lot different than you, you’ll know that you are 99.9% identical genetically. This kind of knowledge is invaluable to you as you contribute to your own culture and the human geography where you live.

[1] https://www.britannica.com/topic/phoneme

[2] https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Phonemic-Diversity-Supports-a-Serial-Founder-Effect-Atkinson/ebc734345ee569b116de14ed77fb5b09230c68ea